Ethiopia

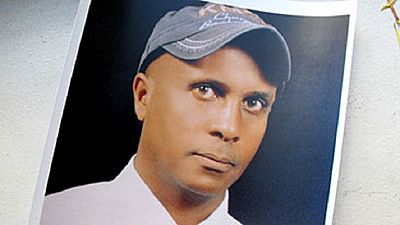

More than six years in jail have not blunted Ethiopian journalist Eskinder Nega’s criticism of the government that put him there.

He was released in February, as part of a broad prisoner amnesty, and remains just as defiant, just as determined as when he was locked up for writing critical articles.

“I am prepared to go back to prison,” Eskinder, 47, said in an interview in the Ethiopian capital this week. “What I am not prepared to do is give up.”

“We will continue to press and struggle for freedom of expression and democracy.”

Eskinder’s widely-read columns routinely took his country’s authoritarian, one-party government to task, until his arrest in September 2011, after writing a column predicting an Arab Spring-style uprising in Ethiopia.

Like other critical journalists, bloggers, activists and politicians, he was charged with terrorist offences and later sentenced to 18 years in prison.

His trial and detention attracted international condemnation from rights groups, including the literary freedom organisation PEN International.

Despite the recent, unexpected release of thousands of political prisoners, himself included, Eskinder fears life for journalists may worsen rather than improve, following the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) government’s declaration of a nationwide state of emergency last month.

New prime minister, new dawn?

Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn announced his resignation last month, a move unprecedented in the party’s 27-year rule. Behind closed doors, EPRDF leaders are in the midst of an opaque process of selecting a successor.

Whoever is chosen, Eskinder said an essential first step will be a willingness to talk, even to the party’s enemies, if people are to believe democracy is growing.

“If that person wants to make change, wants to make real change in this country, he will have to engage in negotiations with all political parties, including those who have been branded as terrorist organisations,” he said.

Democracy rising?

The prisoner amnesty that saw his release was described by Hailemariam as aiming to “improve the national consensus and widen the democratic platform,” but analysts saw it as a reaction to popular anti-government sentiment.

Months of destructive, sometimes deadly, protests began in late 2015 and only stopped after the imposition of a 10-month state of emergency in October 2016.

Africa’s second-most-populous country remains a hard place for the press, ranking 150 out of 180 countries on Reporters Without Borders’ press freedom index.

After first travelling to the United States to reunite with his wife, who moved to Virginia with his 11-year-old son while he was jailed, Eskinder is considering a shift from print to broadcast journalism in a bid to reach a wider audience.

“To be relevant to the struggle, I think involvement in satellite television is fundamental,” Eskinder said.

But while the medium may change, the message remains the same: “It’s western liberal democracy that I envision for the country.”

00:58

Somaliland opposition leader wins presidential poll

01:00

Somaliland counts votes after pivotal election

11:07

Botswana's new government races to diversify its economy {Business Africa}

Go to video

RSF urges Sahel States to sign declaration protecting journalists’ right to information

00:56

South Sudan's peace monitoring body meets to discuss election postponement

Go to video

Algeria: Journalist Ihsane El Kadi obtains presidential pardon