Liberia

Over two decades ago more than 250,000 civilians were killed during Liberia’s civil war. Most combatants didn’t choose to join the war. They were forced to fight by conscription or desperation. Despite this, society now stigmatises them for their active role in the violence.

In this episode, we explore the role of traditional masculinity in Liberia’s civil war. We talk to former soldier Jonathan about what is expected of men who go to war and how masculinity was pushed to the extreme.

“I really, really enjoyed it like I was playing, like a dream. I cannot believe that I got a gun in my hand to kill somebody. To take somebody's life,” Jonathan says.

This is a story of young men who picked up their rifles when they had nothing left. They obeyed orders, and stood on the frontline of battle. These soldiers did not shake when they had to pull the trigger, because they were not allowed to be vulnerable.

Their training is full of catchphrases about masculinity: Be brave! Be strong! Be a man! For this reason, the recruitment and training process for soldiers is linked to the idea of how a ‘real man’ should behave.

The problems start when masculinity becomes toxic. It is then that manhood is taken to the extreme, at the expense of everything, especially women.

Up to 70 per cent of the population during Liberia’s civil war suffered from some form of sexual violence during the conflict, according to Amnesty International.

In this episode we also speak to Bernice Freeman, from Liberia’s Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET), which was created in 2002 to stop the killings. Racheal Wanyana, Uganda Gender Advisor with the Saferworld organisation also weighs in on the topic.

Like this episode? Share your thoughts on how you have challenged your view on what it means to be a man using the hashtag #CryLikeaBoy. And if you are a French speaker, this podcast is also available in French: Dans la Tête des Hommes.

Please do not hesitate to listen and subscribe to the podcast on euronews.com or Castbox, Spotify, Apple, Google, Deezer, and give us a review.

THE SOLDIERS OF LIBERIA: A MEN’S WAR - TRANSCRIPT

Danielle Olavario [Disclaimer]: Before we start, just a heads up that this episode contains testimonies and stories of war that some listeners may find upsetting or disturbing.

Danielle Olavario: Liberia: the smallest country of West Africa. With 580 kilometres of coastline stretching along the Atlantic coast, it’s a paradise for tourists and surfers alike. The country boasts a tropical climate, a sea full of fish, and golden beaches. Today, if you were to take a stroll on one of those beaches that dot the shoreline, you’d hardly think of what happened here.

Freeport, Liberia’s main harbour. This used to be a very strategic spot during the last years of a long civil war that ravaged the country between 1989 and 2003.

Jonathan G: [he recreates a war sound]

Carielle Doe: What's that sound?

Jonathan G: That's a machine gun approaching the point. Then they will reply, from what the Freeport [he recreates another war sound]

Jonathan G: You stand right here on the beach, see, people carry people in the water.

Danielle Olavario: Jonathan G, a former Liberian soldier in his late forties, recalls the sound of a battle that took place here. He doesn’t want us to use his whole surname as he is still afraid of the consequences of his involvement in the war.

When we first met him, Jonathan gave us the impression of being a laid back guy. This changed as soon as he started to talk about the war. Like water has strong currents underneath a calm surface, Jonathan had another side. His expression revealed that he had experienced violence at its worst.

Most of his fellow ex-combatants didn’t choose to join the war; either by conscription, or desperation, they were forced to do so. But Jonathan always knew that he wanted to be a soldier: he had always admired his uncle, a high-ranking military man.

He told us when he was about 13, he saw the execution of a failed coup participant at the military barracks. And he thought: ‘that is power’.

And when the war started, he wanted to be part of it.

Jonathan G: We need to fight to get back to our home. So is our home and the people that brought the wars are killing us. We need to go back and kill them too, even to squash the whole family.

Danielle Olavario: But he does acknowledge that when he saw himself caught in the middle of a war, he was afraid of dying.

Jonathan G: We were all scared to go in a time when you are part of those armies, you get killed.

Danielle Olavario: Just like in several other cultures, in Liberia when men go to war they must be strong, all-powerful, invincible and merciless.

Jonathan G: I never had a weakness. I never had weaknesses. All I knew was what I was told to do and I did it.

Danielle Olavario: Welcome to Cry Like a Boy, a Euronews podcast where we travel to five African countries to tell stories of men defying centuries-old stereotypes.

I’m Danielle Olavario and today we are in Monrovia, the capital of Liberia. We are also going to travel in time. Here, over two decades ago where more than 250,000 civilians were killed during a civil war. Many died during the battles, others died of hunger, and many thousands more had to flee from devastation.

The protagonists of our story are the soldiers behind the fighting. Men of all ages caught up in the spiral of violence. Sometimes they were perpetrators, and sometimes victims. Today, society stigmatises them for their active role in the killings.

Yet this is not only a story about Liberia. This is a story of young men who picked up their rifles when they had nothing left. They obeyed orders, and stood on the frontline of battle. These soldiers did not shake when they had to pull the trigger, because they were not allowed to be vulnerable.

This is a story of what is expected of men who go to war.

Jonathan G: It makes me feel like a man and brave that if these men can do this, I can do it, too.

Danielle Olavario: Founded in 1847 by freed American slaves, Liberia was once among Africa's richest countries. Its wealth came from its many natural riches: gems, valuable hardwood trees and rubber plants.

Until the war tore everything apart.

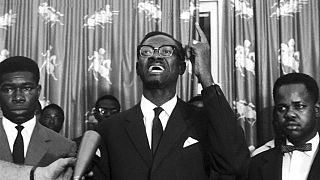

The war began in 1989, when an armed group belonging to Prince Johnson, a former Charles Taylor commander, assassinated the then president Samuel Kanyon Doe. The assassination was filmed and well documented. Yet the uprising against President Doe was quite popular as Liberians were fed up with how despotic and dictatorial his administration had become.

The resulting power vacuum intensified the fighting between armed groups. The guerrilla war spread to neighbouring Sierra Leone and eventually involved Burkina Faso and Libya. Natural resources, age old inter-ethnic tensions and the wide gap between the rich and the poor fuelled the conflict.

Danielle Olavario: Charles Taylor was an active member of president Doe’s government. He then joined the resistance against him, and soon became a warlord. Taylor's forces and the other factions competing to get the power terrorised civilians in Liberia and neighbouring Sierra Leone through killings, rapes, mutilation, pillaging, finally pushing them to move elsewhere in the country.

But, despite his war crimes, Taylor was democratically elected as President in 1997.

"He killed my ma, he killed my pa, but I will vote for him”: This was the slogan used by Taylor supporters in his campaign. Taylor was - and probably still is - a very popular figure among its supporters.

Once elected, Taylor promised to put an end to the war. But during his time in power, the conflicts became harsher. Plus, he festered conflict in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Senegal.

Lawyer: Now, Mr. Taylor, as you are aware, you are charged on an indictment containing 11 counts, which alleges that you are everything from a terrorist to a rapist. What do you say about that?

Charles Taylor: I'm a father of 14 children, grandchildren with a love for humanity. Have fought all my life to do what I thought was right in the interests of justice and fair play. I resent that characterisation of me. It is false. It is malicious.

Danielle Olavario: Taylor underwent trial in 2009 at the international criminal court at the Hague. He is currently serving a 50-year sentence for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Those outside of Liberia who are familiar with the civil war, will surely remember a photograph of that period.

It depicts a very young man, shirtless and wearing low-waisted military trousers. He’s jumping euphorically in the middle of a bridge in Monrovia. In his left hand rests a Kalashnikov. His right hand is raised to the sky in triumph. All around him, the smoke of gunfire. His name is Joseph Duo, and back then he was a soldier like Jonathan, jubilantly celebrating the fact he had hit his target.

World-famous photographer Chris Hondros captured the battle, and transported it from the small African country to the front pages of newspapers around the world.

The image represented the common attitude of young men towards the war at that time.

Jonathan G: I really, really enjoyed it like I was playing, like a dream. I cannot believe that I got a gun in my hand to kill somebody. To take somebody's life.

Rachaeal Wanyana: History is full of examples of masculinity taken to the extreme not only in Africa, but, you know, across the world.

Danielle Olavario: This is Racheal Wanyana, Uganda Gender Advisor with the Saferworld organisation. The organisation focuses on preventing conflict and on peacekeeping. She makes an example of her country, Uganda, where men also glorify war and the figure of the warrior.

Rachaeal Wanyana: And we have also seen in some cultures where men go to war to fight for glory, particularly amongst the Karamajongs they have warriors who go to war so that they are respected in society because society in their communities has attributed a certain form of valour to being a warrior.

Danielle Olavario: Military training is like choreography. A process aimed at breaking down individuality and creating a group of men that respond in unison. Their loyalty becomes unwavering. They’re bulletproof.

Jonathan G: As a soldier, once a soldier, always a soldier. If I ever hear a gun firing, I must move to where the gun is firing.

Danielle Olavario: Their training is full of catchphrases about masculinity: Be brave! Be strong! Be a man! For this reason, the recruitment and training process for soldiers is linked to the idea of how a ‘real man’ should behave.

Rachaeal Wanyana: I would say is more of a strategic move because to gain potency and wider acceptance, the military has to align itself with the dominant or the hegemonic norms and values system of the community which it inhabits.

Danielle Olavario: Studies suggest that the ability to suppress fear enables soldiers to engage in combat. This in turn helps them to come to terms with the idea of putting their lives at risk everyday. They turn into machines that can silence compassion and empathy. This in the end allows them to perpetrate violence against their enemies.

Racheal Wanyana: Many times in these times of conflict, the men are struggling to live up to societal expectations of masculinity, being able to provide for their families, being able to protect the women whom they find are vulnerable and ought to be protected by them. So the appeal or the manipulation of these hypermasculinity qualities offers these men who feel emasculated, a way of reclaiming their masculinity.

Danielle Olavario: The problems start when masculinity becomes toxic. It is then that manhood is taken to the extreme, at the expense of everything. Especially women.

Racheal Wanyana: Thinking that men are entitled to women's bodies and as such, they feel that they kind violate them at will, this explains why there is there there is mass sexual violence against women during conflict and the primary perpetrators are men. It explains why women, women's bodies are seen as a battleground by men.

According to Amnesty International, in Liberia up to 70 per cent of the population suffered from some form of sexual violence during the conflict. The UN believes the numbers are probably a lot higher, as many rapes went unreported.

This stopped when Liberian women couldn’t take it anymore.

Bernice Freeman: Well, I decided enough was enough. They are killing our mothers, our fathers, our children being killed and raped. We cannot sit and our values, our children, our husbands being taken away. We must stand up as women.

Danielle Olavario: This is Bernice Freeman, from The Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET). We are at their headquarters in the Fishmarket area in Monrovia, a very central one. This group was created in 2002 to unite Liberian women of different religions and backgrounds with a common goal: to stop the killings and demand peace. The uniform of that group is normally t-shirts and lappa, aka patterned african cloth, and their heads are tied.

Bernice Freeman: And we stood up.

Danielle Olavario: Bernice is short, very dark skinned, she wears a braided wig that she pulls back. She’s a leader, the women listen to her.

Bernice Freeman: We took to the streets. We started mobilising. We wanted to do this. Can we mobilise? And you know the joy of the Liberian women mass action for peace. Most of the women that came on board had a story. So you will be there for me, I will be there for you because our stories were similar. We were united because we were going for something. We were not scattered. So I joined the mass action because I was tired of the men being our perpetrators. Killing us.

Danielle Olavario: Liberian women staged non-violent protests to pressure both sides to abide by an unconditional ceasefire. Their contribution was instrumental in bringing about peace.

Although the war is over in Liberia, there are wounds that are still open, unhealed.

Most of the crimes perpetrated during the war went unpunished. People sometimes bump into the murders of their relatives or their violators in everyday life, for instance while going to the supermarket.

Bernice Freeman: We have two women here. That woman had a daughter, the only child she had. And she was friendly with another woman, not knowing the woman she was friendly with the woman whose son was the killer of her only child.

Danielle Olavario: In the next episode of Cry Like a Boy we will delve into the invisible wounds of war: the wounds of the mind. These wounds don’t bleed, but are harder to heal. And they grip Liberia's future.

Liberians have endured a lot over the past decades, but few have the "luxury" of acknowledging that they are traumatised. Let alone seeking help. Especially the men. Liberian men are not allowed to talk openly about it, because "real men" are not allowed to show their weaknesses. Or are they?

CREDITS:

Danielle Olavario: You are listening to Cry Like a Boy. If you’re new to the series, check out our stories on redeemed husbands from Burundi, gay men from Senegal, traumatised miners from Lesotho and fallen migrant/heroes from Guinea: All African men fighting to defy the strict gender roles and rules. You can visit our website for more original content, videos and opinion pieces. I, Danielle Olavario, will see you on our next journey.

In this episode, we used music by Liberian artist Faith Vonic. You can find out more about her music in her Youtube, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter accounts.

We also used archive files of the Liberian war from the news agency AP and the Nobel lecture of Liberian former president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf from the NobelPrize.org.

With original reporting and editing by Carielle Doe in Monrovia, Liberia. Marta Rodriguez Martinez, Naira Davlashyan, Lillo Montalto Monella & Arwa Barkallah in Lyon, Mame Peya Diaw in Nairobi, Lory Martinez in Paris, France and Clizia Sala in London, UK.

Production Design by Studio Ochenta. Theme by Gabriel Dalmasso.

Special thanks to Peya Mame and Natalia Oelsner for discovering the music for this episode. Our editor in chief is Yasir Khan.

For more information on Cry Like a Boy, a Euronews original series and podcast go to euronews.com/programs/cry-like-boy to find opinion pieces, videos and articles on the topic. Follow us @euronews on Twitter and @euronews.tv on Instagram.

Our podcast is available on Castbox, Spotify, Apple or wherever you listen to podcasts. If you liked this episode, please rate us and leave a comment. We love reading those.

Share with us your own stories of how you changed and challenged your view on what it means to be a man. Use #crylikeaboy. If you’re a French speaker, this podcast is also available in French: Dans la Tête des Hommes.

11:05

Africa's hight cost of climate change [Business Africa]

01:17

COP29 finance talks lag as the summit reaches its halfway mark

01:38

COP29: What next for Africa's energy transition?

01:00

Civil society takes center stage at Brazil’s G20 social summit

01:58

Climate adaption: Unfulfilled pledges mean “lost lives and denied development” – UN chief

Go to video

Vladimir Putin affirms "full support" for Africa